Every week, we'll be sitting down with one of our gallery artists to discuss their work, process, inspiration, and stories. This week we're speaking with Tamar Zinn.

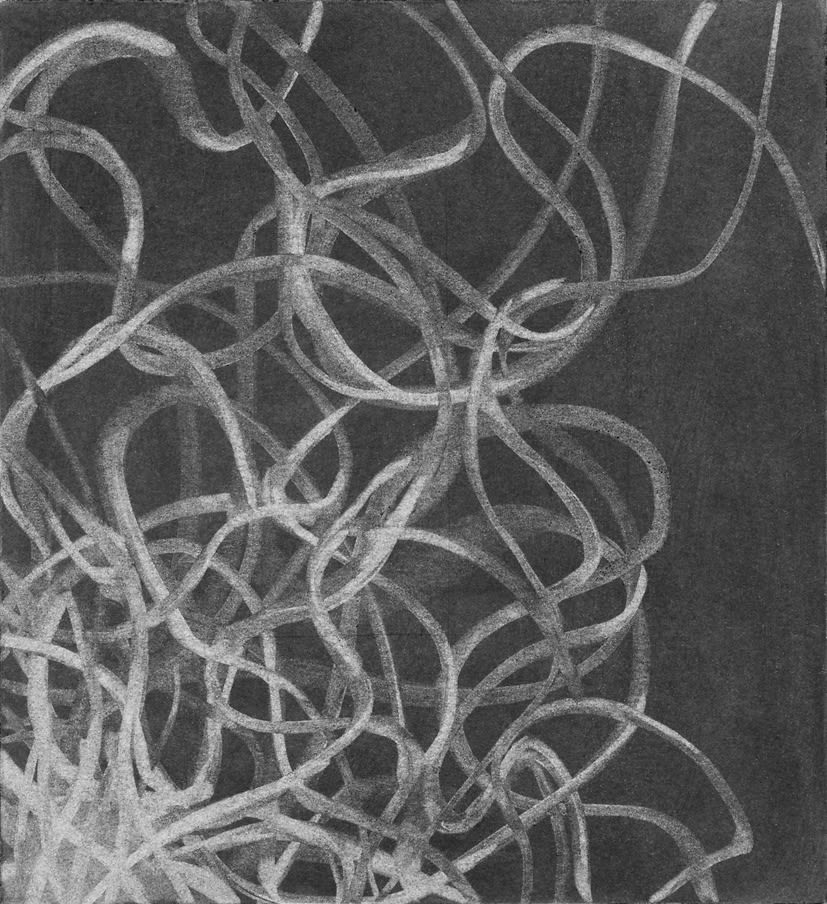

"At the Still Point 6"

Tamar Zinn's latest series, "At the Still Point," which will be the subject of a forthcoming exhibition at the gallery, is exploring the culminating moment when the compositional tension of the work both activates and crystalizes the space. The geometry is revealed by the building up and scraping away of layers, working methodically in horizontal and vertical movements across the plane, until a moment of clarity is reached. The result is a field activated by depth and dynamism, the relationship of geometric elements and ambiguous space. We headed downtown to Zinn's studio to discuss tracing the evolution of an artist's visual vocabulary, balancing intuiton and intention, and discovering your paintings in poetry.

What are your earliest memories relating to art?

As a child we went to museums all the time. We went to MoMA, we went to the Met, we went to the Guggenheim. But I think the first time I really felt a connection with what I saw at those museums was in elementary school. I had made a paper maché mask, and there was an exhibit at Lever House on Park Avenue of art by public school children, and my mask was one of the pieces in the exhibit. While I didn't realize it at the time, that was probably when I sensed that someone like me could make something that gets put in a special place. A few years after that, when I was in sixth or seventh grade, I started going to Saturday classes at the Art Students League. That was when I was drawing from the figure and I became very aware of gesture, of moving my hand, of the connection between my actions and transforming what I was seeing. So, those are the earliest memories, but I never thought of it in terms of becoming an artist. I had absolutely no idea.

When did you get that idea?

Well, it wasn't until a few years after I graduated from college. I was a classically trained violinist and I was seriously pursuing music, so in college I started out as a double major in classical music performance and in art. After maybe a year and a half, I sensed that music was going to take a back seat to art. I continued to play chamber music, but I was much more excited about art. Even then, I still didn't think, "I'm going to be an artist." I had absolutely no idea what I was going to do with my life. I just painted because I liked to paint. The first realization that it was something more to me was maybe two or three years after I graduated from college. I went for a residency at a place outside of Woodstock, because I wanted to see what would happen if I spent a month where no one was telling me what to make or how much time to spend at it. I was ecstatic. I was spending 14 or 15 hours a day in this barn, just painting away. It was wonderful. A few months after that was when I had the nerve to bring some watercolors up to Kathy Markel when she had a gallery on 57th St, and to my amazement she said "Sure, I'll take some of those." So, becoming an artist just came out of doing it. I never really thought "Oh, this is what I'm going to do. I'm going to be an artist."

Who have been some of your influences?

First and foremost: Morandi. I see him as someone who, even though he's painting still life, has the mind of an abstract artist because of his repeated investigations of the same forms, his study of the relationships between the forms and attention to positive/negative space. I always find great joy in looking at his work. In terms of other people working today: Brice Marden. I spend a huge amount of time with his work. Suzan Frecon, particularly her works on paper. Stanley Whitney because I'm infatuated with the clarity of his colors. Then going back in time, I was spending a lot of time staring at the work of Richard Diebenkorn way before I had any understanding of abstraction or any hint that my work would ever move in that direction. Going back further there's Mondrian, Manet, Matisse, and then Vermeer, because of his handling of light. Those are the people I go to in a tough time when I feel stuck. I'll pull out books of their work and it gives me the courage to face my own work again.

A lot of your work is very geometric or mathematical - although I'm not sure if you'd call it mathematical in particular - and I was wondering if there was something in your background that caused you to be interested in that, or if that was part of your upbringing in some way?

First thing, there's zero connection to mathematics in that nothing that I do is planned or measured. Everything that emerges is very intuitive. I never measure anything. I'm never calculating anything. Rather than mathematics, I think there's an awareness of structure. While I'm not sure if this has any direct connection, my father was an architect, my son is an architect, and my husband is a photographer who has spent a lot of time photographing architecture, often from high above the city looking out. I think I have a sense of design and structure that's always been in my work.

I did invented landscape imagery for quite a few years before moving into abstraction around fifteen years ago, and even in that work I found ways to impose structure by scraping off the edges of my images, or making wide panoramas that were broken into segments. The earliest work that I showed Kathy many decades ago was in watercolor, but the way I worked was that I would draw horizontal bands and vertical segments and paint very loosely within each band. So that tendency to impose structure onto things that are very fluid has always been there, even if it wasn't something I thought about.

It's interesting to me that who we are as artists is present in the very early work, but we often don't recognize why we're doing it. Elements of a personal vocabulary are there for a while and may go into quiescence as other things take over, and then they'll come back. The vocabulary that seems to matter to us visually, if you look back, you'll often find it was there all along.

This seems like a natural progression to talk about your process.

My paintings start with layering, in a very methodical way, broad flat areas of color. Under many of these paintings that end up in shades of whites and grays, there are some really intense colors in the early layers, a lot of really rich reds or blues. Since I'm working on aluminum composite, which is very smooth, I brush on the paint in perpendicular layers so that I'm slowly creating a texture in the surface. There's no geometry at all at the beginning. After a while, I have a sense of where the palette may go, whether it's a sort of blue-gray or a yellow-gray, and I start dragging the paint across with different scraping tools in horizontal and vertical movements. I'll also coarsely sand some areas in those same methodical horizontal and vertical motions. That's how the atmospheric layers emerge across the entire surface. There's still no geometry in these early layers.

Then at some point, and I don't know why it's at that point, when the surface is wet I'll start scraping off sections and some structure begins to emerge. It's always at the edges. I'll scrape off another edge, and one thing leads to another. If there's a rectangle in one spot then I start thinking "Okay, what's going to create tension with that?" Finding the composition is a process of removal rather than painting over. When I sense that the compositional tension is getting stronger, the entire surface becomes re-engaged. Everything is in flux as I react to these structural elements as they emerge.

The most terrifying part is when I realize it's time for one of these dark bands at the edge. Since I don't work mathematically, I never really know how thick it should be or how long it should be, and there are certain stages in the painting where if I do something and it doesn't quite feel right, it takes a lot of work to backtrack. So there's a certain amount of risk and I need to wait for the days where I have the confidence to tackle that.

Even without knowing that some of these start with a very rich, colorful base, you can see while looking at them that it's not just gray, that there's a depth of color in there. But in the end at least the initial impression is that it's a neutral palette. Was there any kind of conscious decision to anchor this series in that palette, or was it just how it developed naturally?

Where I end up is a balance between intuition and intention. The paintings all start out without a direction, but of course I am making decisions on some level. Whatever gets put down intuitively I have to interact with, and it's going to lead me to where I'm going next. One thing, though, is that when I go to galleries and museums I notice what I'm noticing, because it often is a clue to what's rumbling underneath the surface for me and what may be coming next. What preceded all of this achromatic work was that for a year or two I was noticing all the whites, no matter whose paintings I was looking at. I just kept thinking about how other artists were using white, and that became a preoccupation with what whiteness was about and how it actually has infinite manifestations.

I think some artists may feel that they direct their work. I feel that the work directs me. Those underlayers of saturated colors, I think, are a bit of my longing for more color to be there, but it will happen only when it's the right time.

I also wanted to ask about your Tangle series, since some of it was shown in "Humble Iterations" earlier this year. Looking over your work from the last couple of years, they're a departure for you, and I was wondering if you knew what that urge was to explore gesture more. You were mentioning gesture in your earliest works, but why now?

I started doing that work about three years ago because I really missed gesture; I really missed the movement of my hand. My paintings are about structure and geometry, and I missed that physical sense of mark making. The other thing was that my painting process is very, very slow. I wanted to work in a way that I could do quickly. I build up a blackish field with several layers of charcoal, rubbing it into the fibers of the paper, and then I work with a kneaded eraser as my drawing tool. So I draw through a process of removal. It was very satisfying, very meditative, like I was taking a slow breath. My rule was I couldn't go back-the drawing was finished when the gesture ended. With the paintings I could just keep going on and on and on, and these charcoals are very immediate. When they're done, they're done.

With my newest series of charcoals, "Tracing Stillness," I wanted to see if I could draw just one good line in a field. It came from my interest in slowing down the work. It was the most challenging thing I have ever done. With one line it's got to be just right. I can't tell you how many failed attempts I had. The gesture is very slow, and I have to balance letting my hand go where it wants to go and feeling like I have some sort of control.

I wanted to talk a little bit about titling your work. For your upcoming show, "At the Still Point," you got the title from a T.S Eliot poem, "Burnt Norton." What was the process for naming the show? Did you find the poem first and that inspired the series, or was it the other way around?

When the first group of these paintings, the smaller ones, neared completion last fall I realized I needed to name the series. I do not enjoy coming up with titles. Occasionally something comes to me, but this time I was completely at a loss. A very close friend who is an artist and also has a very strong background in literature and poetry came over and we chatted about the work. She asked me a lot of questions about what I felt was going on and what was behind the work and then she said, "Well, I'm not sure if I'm quoting this exactly," - turns out she was doing it perfectly - "but the way you're talking about activating the atmospheric fields by the juxtaposition of the geometry, maybe this sounds right to you." And she quotes those five or six lines from "Burnt Norton."

"At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance."

T.S. Eliot, "Burnt Norton"

When I heard it, I immediately knew it was a perfect match in terms of someone putting into words what I felt I was trying to accomplish. I loved this notion of the still point not being a point of stasis, not being a point of balance and harmony, but this unstable moment at which what is on the surface becomes activated and can actually come alive. In the catalogue essay for the exhibit, Mark Wethli elaborates on those connections in a way that I couldn't have done myself. It turned out he was very familiar with the poem.

What do you think the work that's in the show represents about the evolution of your work as a whole?

For twenty, twenty-five years, I had been working with invented landscape imagery - some of which dipped into abstraction but was definitely about nature. My first abstractions were clearly about light and framing light, and those series were called "Scrim" and "Windows". But then as I became more attentive to the geometry, I very consciously eliminated references to light and nature. I needed to do that to better understand the importance of the structure. I was surprised, and initially fought it a little, when I realized that luminosity had come back into the work with this series, and I was also a bit uneasy about the work becoming too pretty. I had to find the balance between the strength of the geometry and understanding what I was doing in the fields, and I had to allow that luminosity to play its role.

Part of who I've always been as a painter, that connection to the natural world, seems to have come back in a different form. Now it is combined with structure, which was also there from the very beginning, but wasn't as strong. So I feel like it's a coming together, a rebalancing, of two central preoccupations that have been in my work for a long time. There's satisfaction in that.

"At the Still Point 23"

Explore more of Tamar Zinn's work here.

Learn more about "At the Still Point," Zinn's upcoming exhibition, here.

Comments

I enjoyed this so much Tamar and wish you all the best for this current exhibit.

These "conversations" are wonderful, at least for me.

Congrats and all good luck,

Diane

I enjoyed this so much Tamar and wish you all the best for this current exhibit.

These "conversations" are wonderful, at least for me.

Congrats and all good luck,

Diane

I am strongly attracted to your work and your honest and generous discussion seemed a faithful complement to it -- quiet attention and tension. Thank you.

Thank you Tamar. This is a thoughtful lecture for me to know

about your background and thinking and how you arrived at this solid

plateau in your work.

I can go back and read parts again.

Best,

Paula