Every week, we'll be your guide as you navigate the world of buying art in our series, The Collector.

There can be a misconception that prints are not as prized as paintings or works on paper, but collecting prints certainly has its own joy. Of course, there are many different kinds of prints, and it's important to be able to distinguish those that are of genuinely good value rather than just a mechanical reproduction of an original work. But, a good, artistically viable print can be seen as an extension of their entire artistic vision. More and more often, respected artists are making prints because they see them as an integral part of their work. Also, a print very often has a substantially lower price than its counterparts on canvas. If you're interested in prints, here's a guide on how to get started.

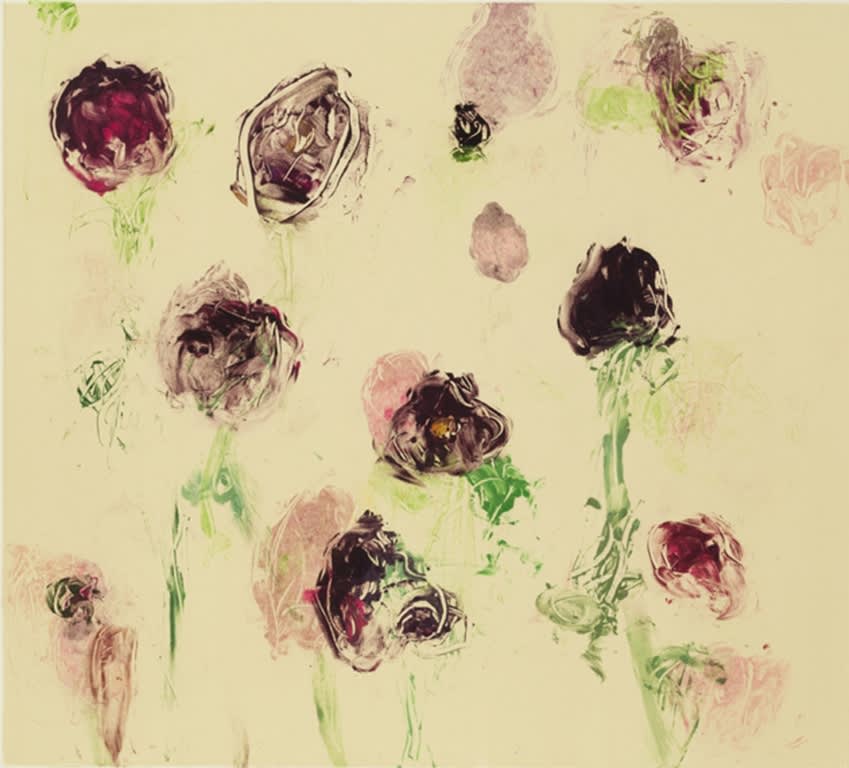

"Purple Lake 12," by Susan Hambleton (monoprint)

First, it'll help to understand the basic terms you'll need to know in order to navigate the world of prints. A good place to start is differentiating between a print and a reproduction. A reproduction is, most simply, a copy of another work. It aims to be an exact replication and is usually not done by the artist of the original piece. Printmaking is a deliberate artistic process that's done by the artist, and the differences throughout the run of prints is integral to the medium. Sometimes they are manipulated to be very different, like changing colors, and sometimes it is only the subtle changes that happen due to the nature of the process. Reproductions do not have much value, while original prints do. Printmaking has a vast vocabulary, but in general prints can be broken down into a few different categories. The different types of prints are determined by how the artist manipulates the matrix, or the object that hosts the image with which the prints are made from.

There can be physical changes made to the matrix such as:

- Etching/engraving (intaglio), where the artist carves into a metal plate with a stylus. They then spread paint across the plate and wipe it away, leaving the ink lodged into the lines behind. A piece of paper is put on top of the plate and it's run through a press, which transfers the ink to the paper just as the artist has drawn it. Typically, the ink is slightly raised on the paper.

- Woodcut (Relief), where the artist carves away everything but the image they want to print. Ink is rolled onto the surface of the image in relief, and transferred to the paper in a press. Think of this technique just like a stamp. The material of the matrix can change. For example, there are also linocuts, which is another type of relief printing made from a piece of linoleum, usually backed by a piece of wood.

There can be chemical changes made to the matrix like:

- Lithography, which relies on the chemical opposition of oil and water. The artist uses an oily medium like a wax crayon to draw their image on the matrix, then washes it with water and applies an oil-based paint or ink to the plate so that it is repelled by the water and only adheres to the drawn image. Paper is placed on top and the plate is run through a press.

Prints can also use techniques from stenciling, like in the case of:

- Silkscreens, where the artist marks off all but the image they want to print on a piece of mesh stretched across a frame. Paper or other material is placed under the silkscreen and ink is pulled across the screen, transferring through to the material in the image of the design. If there's more than one color in the print, a different screen is created for each color.

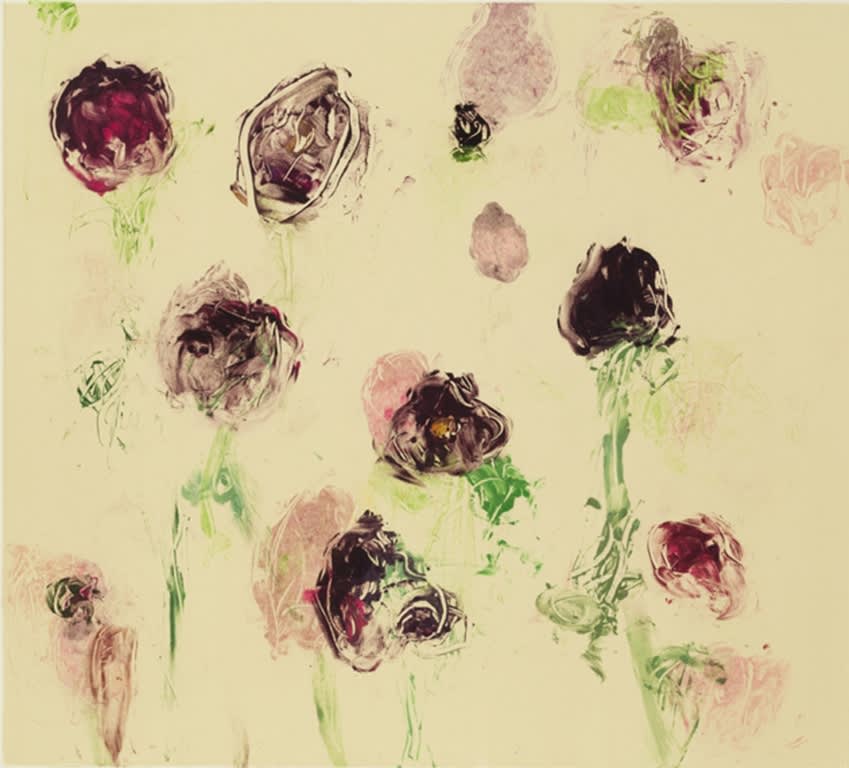

"Autumn Splash" by Jeri Eisenberg

Along with the different techniques, there are a couple of other terms used to identify a print:

Edition:

When artists make prints, they predetermine how many they're going to make of a single image at a specific size. This is called an edition. Each edition print will be individually numbered (3/10 means that it's the third print in that edition of ten impressions), signed, and dated. This information will either be on the print itself, or on a separate certificate.

Limited Edition Print:

A limited edition print should mean that only a certain number of those prints exist, but it doesn't always, thanks to those shady dealers again. Some state laws don't prohibit publishers from printing more copies of the same image, even after they've reached the number of prints stated in the original edition. So, if they change something slightly about the original image - like the size, type of paper, printing technology, or even just calling one the American edition and the other the European edition - they can still claim it's a limited edition. When the appeal is an image's rarity, this practice devalues each print.

Proofs:

The images that are created when an artist, printer, or publisher is testing their matrix or printing process is called a proof. Traditionally, proofs are used as rough drafts of the final image and have notions made by the artist for adjustments in color, design, or the technique. The allure here is the opportunity to get closer to the thinking of the artist, and its uniqueness, so they're typically more expensive than the works in the regular edition.

Monoprints versus Monotypes:

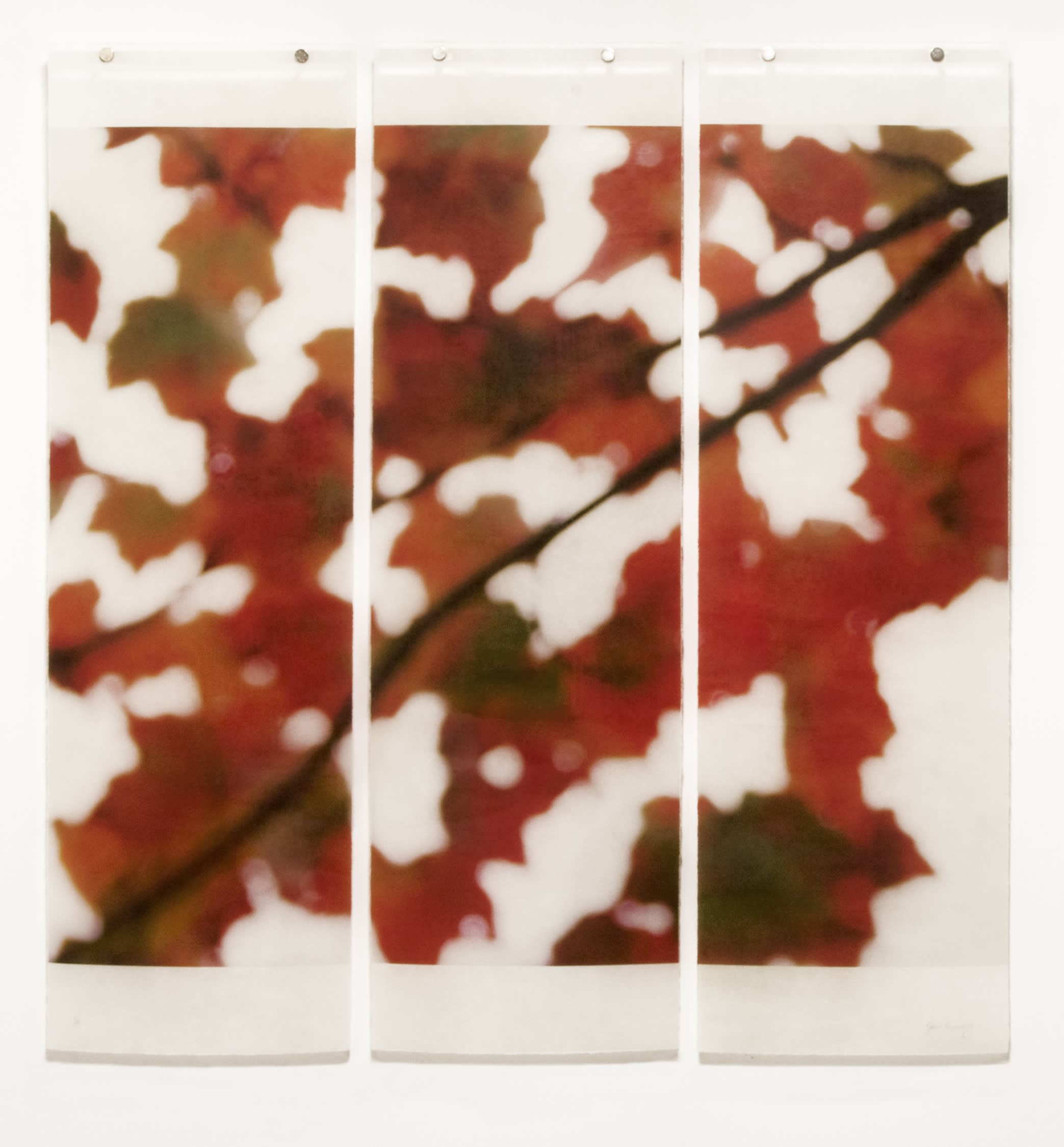

These terms can often be used interchangeably, but there are important differences. A monoprint has a single source for the image (like an etching), and is created by hand coloring or surface alteration. Each monoprint is unique. While there may be a series of similar monoprints created from the same image, they would not be identical. A monotype, on the other hand, do not have a repeatable matrix. A thin film of ink is rolled onto a blank plate onto which the artist directly creates the image by drawing into it or selectively rubbing parts of it off.

"Twilight," by Lisa Breslow (monotype)

You'll also have to navigate some other information when buying a print, and many people are confused about what, exactly, is important when determining the print's value.

- Is the number on the print important? No, the number of the individual print does not affect its value. In the typical printing process, no one keeps track of which sheet of paper is first or last off the press. In etching, it's necessary to keep your paper damp to better absorb the ink. After the print is pulled, it goes on a drying rack to dry out, causing the sequence of paper to become all confused. In color prints where the paper goes through the press a separate time for every color, the one sheet could be the first for the red plate and the last for the blue plate. So, the number doesn't really reflect anything in particular about the print.

- Is the number of the total edition important? Sometimes it's very important. For older prints, there was a physical limitation as to the number of impressions an artist could pull from a copper plate. The later impressions pulled from that plate became weaker as the copper wore down under pressure from the press. So, a smaller edition actually accurately reflected the rarity of the print. Nowadays the plates are given a steel coating to protect them and can be editioned infinitely. You can see how many prints were made, and a smaller number of prints for a contemporary edition can be considered more valuable. But, thanks to the trickiness discussed in what a limited edition print even means, you can't always trust that edition number.

- Is a signature on the print important? Not necessarily. Prior to the printmaking boom in the late 19th Century, many artists considered their printmaking unimportant (as did the marketplace) and didn't bother to sign their prints. Rembrandt etchings are never signed, for example. Even if an artist has signed the print, it doesn't always mean they had any input into their creation, that they're original, or that they have any value. But, a signature is a very helpful indicator that differentiates a fine print and a well-framed poster.

"All in the Waiting IV," by Yolanda Sanchez (monotype)

There are also some other factors that determine the print's value, namely:

- the size

- the date (whether or not it fits into a particularly important period of an artist's career or era of printmaking)

- the condition: prints' colors can fade over time, or the paper can deteriorate

As always, with some preparation and open discussion with your art dealer, you'll be assured that you're adding a genuine, worthwhile, and valuable print to your collection.

Comments

Wow, I had no idea that there was so much involved when it cam to buying prints like these online. I'm especially impressed to learn that there are so many types of prints like limited editions and proofs. That is something that I will definitely have to keep in mind if I every decide to buy any of these for my home. https://carterscustomwares.com/

This is a great article on information about original prints. I especially like the section on Monotypes vs. Monoprints, as I have had to explain the difference to those unfamiliar with original prints.

However, I was wondering if you meant to put "mono prints" in this sentence instead of "monotypes": "While there may be a series of similar monotypes created from the same image, they would not be identical."

Thanks for sharing your expertise on original prints.